Is it possible, though, for a non-BJP party or alliance to storm into the saffron fortress? If it is, what role will Dalits play in this political shift?

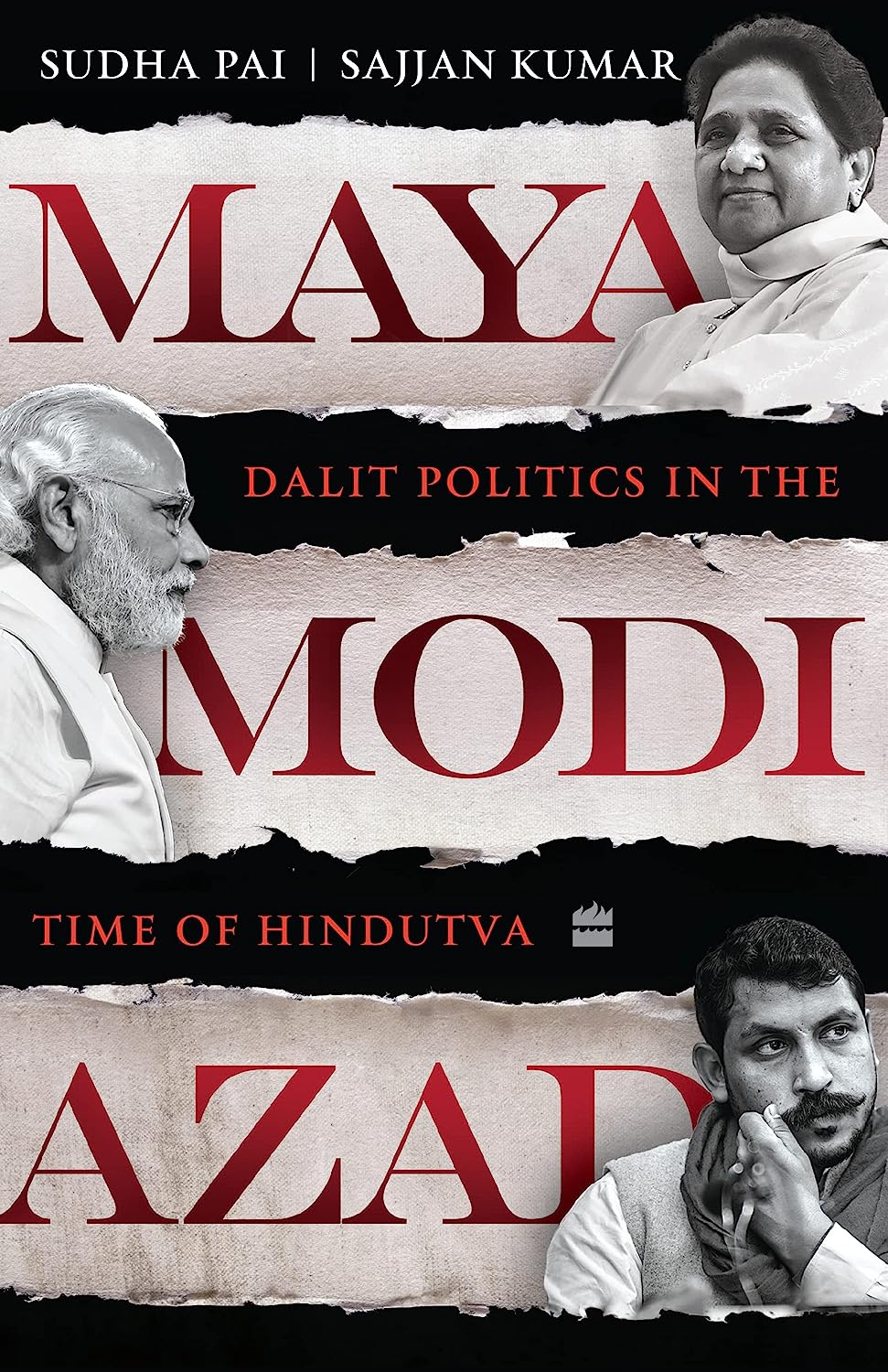

The book titled ‘Maya, Modi, Azad: Dalit Politics in the Time of Hindutva’ by Sajjan Kumar and Sudha Pai (HarperCollins India; Rs 599) is an important read for those seeking answers to these questions.

The book raises some critical questions: What is the future of the BSP and Mayawati? What is the significance of the rise of new Dalit organisations in UP such as the Bhim Army? Why does a section of Dalits today support the BJP electorally and culturally? Will the BJP be able to sustain its subaltern reach and bring all the Dalits into a ‘Maha Hindu’ identity to realise its ideological vision?

The authors have traced Dalit politics back to the mid-1980s when Kanshi Ram founded the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) with his close associate, Mayawati.

The BSP came to power three times in the 1990s with the help of coalition partners and Mayawati was elected chief minister thrice; it was only in 2007, however, that the BSP won Uttar Pradesh with majority riding high on its Sarvajan politics, winning 206 out of 403 seats in the Assembly.

BSP realised that to come to power on its own, it needs to be inclusive and include the upper-class Hindus — Brahmins — as its core Dalit vote was not sufficient to garner the party a majority in the UP Assembly.

Mayawati’s close aides Nasimuddin Siddiqui and Satish Mishra were behind the Sarvajan strategy and had started working on it in 2005. The BSP then abandoned its Bahujan strategy.

This was when the BSP started organising the Brahmin Bhaichara Sammelan and started giving key positions to Brahmin leaders. The strategy paid dividends in the 2007 Assembly election.

In 2007, for the first time in independent India, a Dalit party was able to get a majority in India’s most populous state — and also one of its poorest. Mayawati became Chief Minister for the fourth time.

The 2007 Assembly elections marked a watershed moment for the BSP, with Siddique and Mishra playing a vital role in getting Mayawati a majority and the crown. She had become the ‘King’ in UP politics and everything had started to move around her in the state. However, she soon destroyed her own kingdom with her short-sighted politics and damage her core vote bank — the Dalits.

The authors contend that Mayawati invested heavily in Uttar Pradesh. The Mayawati ‘Sarvajan’ government was undoubtedly one of achievements and did much better than the Yogi regime of 2017-21. The economy was also doing better than it did under the Samajwadi Party (SP) from 2012-2017.

Many expressways inaugurated by PM Modi during his campaign for the 2022 Assembly elections were actually started during Mayawati tenure and continued under the SP government of 2012-17, the authors point out.

But it was arrogance that cost Mayawati her crown. She came crashing down in the 2012 Assembly elections and with it the Dalit community.

Since 2012, Dalit politics has taken a sound beating as the community disintegrated into various parties and the sub-castes were tapped by other political formations, especially by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The authors explain the many factors that led to this disarray. Dalits as a community wanted more spending on better education, roads, health and other facilities, whereas Mayawati wasted large sums of money on building memorial to Dalit icons and dedicating public places in their names, leading to large-scale corruption.

Quoting from their field work which the authors took in the state of Uttar Pradesh for years, they establish that while Brahmins, Rajputs, Vaishyas voted for BSP in the 2012 election, it was actually the sharp decline in BSP’s core vote bank — the Dalit. The BSP could only win 80 seats in the 2012 elections.

Dalits also punished Mayawati for two more reasons — amassing greater wealth for herself and the rampant corruption in the state departments.

After BSP was out of power, the party started to decline gradually with it the Dalit power base. Mayawati became more inaccessible to the party workers and BSP started to lose the party’s organisational structure which took a hit in every district. The leaders who were associated with BSP since the times of Kanshi Ram either started to leave or were expelled from the more susceptible Mayawati. The biggest dent to BSP came in 2017 after Mayawati’s close aide Nasimuddin Siddiqui was expelled from BSP.

Mayawati sold seats in the 2014, 2017, 2019, and 2022 parliamentary and assembly elections and no grassroot worker or deserving candidate was given seats. The members had to pay Mayawati if they wanted to contest on a BSP ticket. The lowest amount a leader was asked to pay was rupees three crore.

After BJP came to power in 2014, the atrocities on the Dalit community started to rise. Mayawati — the so-called protector of Dalits — was nowhere to be seen to protect the community. The Dalits, who once formed the core vote bank of BSP started to distance themselves from the party and from Mayawati in particular after the atrocities on the community.

The author writes that Mayawati not once led a protest against the atrocities, apart from giving occasional statements, which were too little too late. The Dalits, especially the sub-castes, become increasingly disaffected by these gestures of Mayawati.

The indifference of Mayawati to the atrocities committed against the Dalits gave rise to new Dalit parties such as the Bhim Army led by Chandrashekhar Azad and Ambedkar Jan Morcha of Shravan Kumar Nirala, who had started his career in 1993 with the BSP. Nirala had been a close aide of Mayawati since 2007.

Also, the collapse of the BSP was accompanied by a ‘caste dispersion’ or a scattering of the Dalit movement, which is visible along three inter-related axes: sub-caste, ideological and sub-regional.

The authors point out that the Balmiki localities in western UP integrated with the saffron discourse in 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2022. Likewise, the Pasi Dalits supported the BSP till 2012 and since 2014 have been backing the BJP.

The Khatiks, too, have shifted towards the BJP after they felt that the SP and BSP are catering essentially to the Jatavs, Yadavs and Muslims. The Khatiks believed that it was the BJP that helped them during the riots and thus supported the party thereafter.

The enigma that ‘Maya, Modi, Azad’ tries to unravel is why Dalits protest strongly against upper-caste atrocities, but at the same time vote/support the BJP in the elections?

The authors write that Narendra Modi was aware that to gain Delhi he had to win Uttar Pradesh. And to win UP, he knew Dalits had to be on his side. Modi also knew that to win Dalits, BJP has to address their economic conditions.

Under Modi’s leadership, the BJP-led government at the Centre took great care to reach out to the Dalit sub-castes, ensuring free rations and other material gains so that these sub-caste could experience some sort of economic freedom.

The authors also point out that many priests associated with the Ayodhya movement were also not Brahmins. Associating Dalits — for its inclusive Hindutva project — was actually a part of the Ayodhya movement.

Even in the 2002 riots, a large number tribals, Dalits and other poorer sections participated in the attacks on Muslims, which helped develop a sizeable Hindu vote bank, enabling Modi’s victory in Gujarat in 2002. Modi used the same tactic during the 2014 Lok Sabha elections to win Uttar Pradesh.

Added to Hindutva politics was the BJP’s successful online and social media blitz because of which the party gained majority in 2014 in the Lok Sabha and in 2017 and 2022 in the UP Assembly.

The Dalit community in Uttar Pradesh is of the opinion, according to the authors, that Chandrashekhar Azad cannot win an election as his party does not have the organisational set-up and skills that the BSP possessed.

They are voting for the BJP keeping their economic needs in consideration and more so, the BJP gives them protection from Thakur ‘goondas’ of SP.

After the fall of the BSP in 2012, the Dalits got divided into pro-BJP and pro-BSP groups, which often led to conflicts between Dalits and Muslims and Dalits and Thakurs.

The authors write that whenever there was a conflict between the Dalits and Muslims, the BJP leaders were always behind the scene adding fuel to the fire. When the conflict was between Dalits and Thakurs, no BJP leader got involved. But Mayawati was always been missing from the scene and did nothing to protect her community.

(Daanish Bin Nabi can be mailed at daanish.n@ians.in)

–IANS

dan/srb